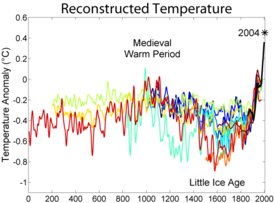

THE LITTLE ICE AGE

The Little Ice Age was a period of cooling that occurred after a warmer era known as the Medieval Warm Period. It is conventionally defined as a period extending from the 16th to the 19th centuries. It is generally agreed that there were three minima, beginning about 1650, about 1770, and 1850, each separated by intervals of slight warming.

Starting in the 13th century, pack ice began

advancing southwards in the North Atlantic, as did glaciers in

For this reason, any of several dates ranging over 400 years may indicate the beginning of the Little Ice Age (while not a true ice age):

· 1250 for when Atlantic pack ice began to grow

·

1300 for when warm summers stopped being

dependable in

· 1315 for the rains and Great Famine of 1315-1317

· 1550 for theorized beginning of worldwide glacial expansion

· 1650 for the first climatic minimum.

In contrast to its uncertain beginning, there is a consensus that the Little Ice Age ended in the mid-19th century.

Northern Hemisphere (

The Little Ice Age brought colder winters to parts of Europe

and

The severe winters affected human life in ways large and

small. The population of

Crop practices throughout Europe had to be altered to adapt to the shortened, less reliable growing season, and there were many years of death and famine (such as the Great famine if 1315-1317, although this may have been before the LIA proper). Violent storms cause massive flooding and loss of life. Some of these resulted in permanent losses of large tracts of land from the Danish, German, and Dutch coasts.

In

In the late 17th century, agriculture had dropped

off so dramatically that "Alpine villagers lived on bread made from ground

nutshells mixed with barley and oat flour.

"

Scottish painting and contemporary records demonstrate that

curling and skating were formerly popular outdoor winter sports, but it is now

seldom possible to curl outdoors in

Southern Hemisphere

Since the discovery of the Little Ice Age, there have been doubts about whether it was a global phenomenon or a cold spell restricted to the Northern Hemisphere. In recent years, several scientific works have pointed out the existence of cold spells and climate changes in areas of the Southern Hemisphere, and their correlation to the Little Ice Age.

In Southern Africa, sediment cores retrieved from

A novel 3000 year temperature reconstruction method based on the rate of stalagmite growth in a cold cave in South Africa suggest a cold period from 1500 to 1800 "characterizing the south African Little Ice age”.

Kreutz et al. (1997) compared results from studies of West Antarctic ice cores with the Greenland Ice Sheet Project Two (GISP2) and suggested a synchronous global Little Ice Age (LIA).

The Siple Dome (SD) has a climate event with an onset time

that is coincident with that of the LIA in the

Law Dome ice cores show lower levels of CO2 mixing ratios during 1550 to 1800 AD, leading investigators Etheridge and Steele to conjecture "probably as a result of colder global climate”.

There is limited evidence about condition in

Paleosea-level data for the

In the Southern Alps of New Zealand, the Franz Josef glacier advanced rapidly during the Little Ice Age, reaching its maximum extent in the early 18th century, in one of the few places where a glacier thrust into rain forest.

Tree ring data from

Although it only provides anecdotal (based on or consisting

of reports or observations of usually unscientific observers) evidence, in 1675

the Spanish explorer Antonio de Vea entered San Rafael Lagoon through Rio

Tempanos (Spanish for Ice Floe River), without mentioning any ice floe, and

stated that the San Rafael Glacier did not reach far into the lagoon. In 1766 another expedition noticed that the

glacier did reach the lagoon and calved into large icebergs. Hans Steffen visited the area in 1898,

noticing that the glacier penetrated far into the lagoon. "the recognition of the LIA in

Climate Patterns

In the North Atlantic, sediments accumulated since the end

of the last ice age, nearly 12,000 years ago, show regular increases in the

amount of coarse sediment grains deposited from icebergs melting in the now

open ocean, indicating a series of 1 to 2ºC (2 to 4ºF) cooling events recurring

every 1,500 years or so (Bond et al., 1997).

The most recent of these cooling events was the Little Ice Age. These same cooling events are detected in

sediments accumulation off

Causes

Scientists have tentatively identified these causes of the

Little Ice Age as decreased solar activity, increased volcanic activity,

altered ocean current flows, the inherent variability of global climate, and

reforestation following decreases in the human population.

Please refer to "MECHANISMS” in the site

menu under Ice Ages.

End of the Little Ice

Age

Beginning around 1850, the climate began warming and the

Little Ice Age ended.